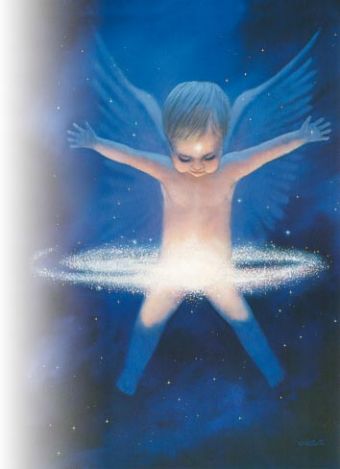

Reincarnation: “When I Was Big”

Again and again, little children are discovered whose ‘band of forgetfulness’ is still permeable, and who can clearly remember a past life. Cases like these have been scientifically researched for more than 40 years. One book looks specifically at European cases.

One fine day in the future, the hard fact of reincarnation will be recognised by the scientific community as a fundamental law of nature. The man who will be honoured by future scientists as the pioneer of serious research into reincarnation is the late Ian Stevenson, formerly Professor at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and the founder of scientific research into re-embodiment.

Unsatisfied with modern, purely genetics-based theories that sought to explain immense differences in behaviour and capability between individuals, Professor Stevenson began to search for the answers to many puzzling questions on his own initiative. In 1960, he heard of a child in Sri Lanka who claimed to be able to remember a past life. He questioned the child and its parents thoroughly, along with the married couple whom the child claimed had been its parents in the past life. Doctor Stevenson was so impressed that he decided to investigate further cases. The more cases he studied, the stronger his conviction grew that there might just be some truth to reincarnation – and the stronger too his desire to see this hidden field opened up to rigorous scientific research. His book, Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, was published in 1966. It detailed his investigations of cases ranging from India to Sri Lanka, Brazil, Alaska and Lebanon.

Professor Stevenson discovered that children first refer to a past life at a very young age (between 2 and 5), but that their claimed recollections fade away between the ages of about 6 to 10. The spontaneous memories belonging to young children are the most scientifically valuable, because it’s impossible to accuse children of having ‘researched’ their memories in historical sources. In around half of the cases, the past life ended with a violent death – with corresponding bodily injuries. In many cases, physical traces of these injuries could be found in the current life – as scars, deformities and birthmarks. Stevenson set about demonstrating a link between these distinguishing marks and the child’s previous life. He considered the numerous matches that he uncovered nothing less than objective criteria for the existence of a re-embodiment. He argued that congenital malformations could only partially be blamed on hereditary factors, viral infections or the effects of chemicals, claiming that 43-70% of cases could not be explained medically.

Stevenson’s critics argued that his examples of reincarnation were all from Asia, where they were spared rigorous examination and lent credence by a cultural background of religious belief in the phenomenon. His 2003 book, European Cases of the Reincarnation Type, pulled the rug out from under them. In it, he detailed the most convincing cases on European soil with masterly precision. Cases of people from England, France, Germany and other countries – where reincarnation does not form part of the standard scheme of life, and where the people concerned were deeply moved by their experiences – had been recorded. We present here four of 22 cases from the book of children who could recall a past life.

Helmut Kraus (Austria)

Helmut Kraus was four years old when he started repeatedly talking about a past life. He would habitually preface his remarks with phrases such as: “Back when I was big…” A friend of the family who regularly brought Helmut home from kindergarten paid particular attention. She described him as “very talkative”. One day, Helmut said to her: “When I was big, I lived at 9 Manfredstrasse.”

Coincidentally, the family friend knew the owner of the house, a Mrs Anna Seehofer, and asked her if she knew of any men who had lived there previously and since passed away. Mrs Seehofer reckoned that Helmut might be talking about her cousin, General Werner Seehofer, who had lived in the house for a while after his first wife had died. Indeed, other statements that Helmut made corresponded to the life and death of General Seehofer.

Werner Seehofer had been an officer in the imperial Austrian army. He rose ever higher in the ranks and was promoted to general in January 1918. During the First World War, he commanded a division on the Italian front, where he was wounded six months after his final promotion. He was captured by the Italians and died soon afterward of his head injuries.

The four-year-old Helmut Kraus (born on June 1st 1931) said that he had been “a senior officer in the Great War”. However, he never claimed to have been a general or mentioned the name “Seehofer”. The most telling pieces of information were the addresses of places he had ‘lived’ during the past life. Along with the address in Vienna that had given an indication of his previous identity, Helmut also correctly provided the address in Linz where his past-life in-laws had lived.

Helmut was four when, walking home with the family friend, she left his jacket unbuttoned, as the weather in Linz was so warm. Helmut insisted that his jacket be done up, for, he said, “an officer can’t just walk around with his coat hanging open.” If soldiers passed by when they were walking along the street, Helmut used to stand to attention and salute until they were gone. On one occasion, Helmut was taken to see General Seehofer’s widow (his second wife). He proved shy in her presence; this was taken to be a sign of recognition, since he was normally so boisterous.

The boy had a marked fear of loud noises, gunfire for example. As the years went by, he developed a clear interest in riding and sport – just like General Seehofer, who had been a “passionate horseman” and had loved sport in general. Helmut continued to talk about his past life until he was about seven, then stopped.

Helmut’s father was a biologist, and the family had no military tradition. Instead of choosing a career in the army, he decided upon gastronomy and took the necessary professional training.

Nadège Jegou (France)

This case begins with the accidental death of a young man, Lionel Ennuyer. A little girl, Nadège Jegou, was to remember his life. Aged 20, Lionel crashed his motorbike, together with a friend riding pillion. He cracked his head on a bench by the side of the road and died almost instantaneously. The friend survived with nothing more than a broken arm.

Lionel’s tragic accidental death sent his mother, Yvonne Ennuyer, into a tailspin of inconsolable grief. She believed in reincarnation, and the hope that her son might be reborn as the child of her daughter, Viviane Jegou, went some way to ease the pain.

Nadège Jegou was born on 30 December 1974 – almost a year to the day after the death of her uncle Lionel – the daughter of Viviane and Patrick Jegou. When Nadège reached the age of three, her mother went back to work, so she spent more time with her grandmother, Yvonne.

Nadège began to speak intelligibly from the age of two. Soon, she began making a series of declarations that demonstrated an intimate knowledge of her uncle Lionel's life. One day, she started talking about his accident as if it had happened to her, quite unprompted. She said that her friend had jolted her and the motorbike had crashed into a bench. She would return to the topic from time to time, seeming to experience it anew on each occasion.