Proteins: The Disregarded Key to Better Health

A lot of people suffer from a chronic protein deficiency, which all too often leads to a number of health complaints. Food alone is not always the answer, but thanks to the latest nutritional research there is now a solution.

Simply put, proteins provide the fundamental building material for the entire body: about half the body mass that does not consist of water consists of protein. Most people these days are suffering from a lack of protein, but addressing the situation simply by eating plenty of meat, fish and milk products may lead to liver and kidney failure. There is only one product in the world that supplies the body naturally with all eight of the amino acids that it cannot produce itself—and without harmful side effects!

Joie de vivre for young and old alike: hop till you drop if the body has enough protein!

Nevertheless, proteins take a leading nutritional position. Almost all the vital substances needed by our body are converted into peptides or proteins from various amino acids (AA). Amino acids are the fundamental building blocks of life; they are transported via the blood to those parts of the body where they are converted and incorporated into the body’s own protein (organ tissue such as skin, musculature, liver cells, enzymes, etc.). Amino acids also form the basis for hormones (e.g. insulin, glucagon) or neurohormones (serotonin, melatonin), as well as scleroproteins (collagen, elastin, keratin), structural proteins (actin, myosin), plasma protein (globulin) or transport proteins such as albumin and haemoglobin. Furthermore, they are important for the production of male and female hormones and the maintenance of a healthy libido.

In addition, they are the foundation for our immune defence system (antibodies, blood clotting factors). Proteins are also required as reserve substances for energy supply in case of hunger. The body regenerates them principally from musculature, the spleen and the liver, where in times of hunger—and also in cases of fad diets or fasting remedies—they are used to supply energy through gluconeogenesis (generation of glucose). Every day the body produces between 80,000 and 120,000 different enzyme connections by stringing together different amino acid molecules and “converting” them into molecular chains of body protein.

Our modern form of nutrition and stressful lifestyle do not always guarantee that we consume and/or make use of all the essential amino acids in sufficient quantities. Our protein requirement is seriously underestimated: as we age, or in times of illness or stress, the body’s ability to absorb nutrients decreases (leading to impaired digestion, a diminished ability to detoxify and the inability to utilise protein). But the amino acid needed to overcome disease can increase to levels similar to what is required by a top sportsman.

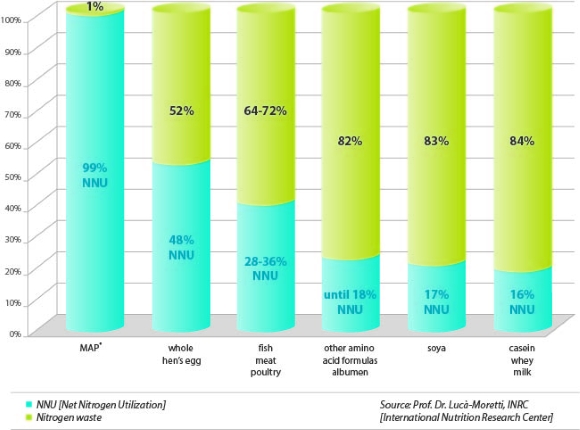

A particular consideration is the nitrogen waste produced through protein food. This consists of the waste products generated by the metabolism of protein (ammonia, urea), which must be disposed of by the liver and kidneys. Only experts understand these connections, and little of this knowledge has entered public awareness. However, the subject of nitrogen waste and its dangers is neglected, even fatally downplayed, in sport and dietary nutrition (the Stone Age Diet, Low-Carb Diet, Montignac) by particular interest groups. The health consequences can be fatal, and not only for people suffering from liver and kidney disease.

At least in extreme sports such as body-building, the protein requirement is well recognised: the recommended intake is based on verifiable practical knowledge and therefore differs considerably from the guidelines of an average nutritionist or the recommendations of the German Society for Nutrition (DGE), or its US equivalent, the Food Standards Agency (FSA).

Nutritional knowledge is not merely in hot demand with regard to the recommended protein requirement for health or sporting performance, but also as regards the potential dangers of an increased protein intake—particularly if we are talking about an inferior protein source, such as those found in modern protein supplements. Countless branches of the economy make their money by marketing these cheap products. Having fallen ill and lacking knowledge as to how such poor health came about, those that regularly consume such products in large amounts are warmly welcomed by our ill-health industry as a good source of income. Dr. Bircher-Benner1 pointed out this situation as far back as 1938, remarking that, “it would appear that man’s most terrible enemy, an enemy unrecognised and unseen, and an enemy that brings about such tremendous suffering, is faulty nutrition.”

But even high-quality protein sources for human consumption such as lean fish, meat and poultry must be carefully considered. Already at the dawn of the 19th century, health problems had become apparent in the case of excessive and unbalanced protein intake among trappers and pioneers in the USA. Their only food source over the long winter months was protein-rich, low-fat wild meat that was also rich in essential fatty acids. Yet in ignorance they neglected to first eat the alkaline-rich offal that any wolf or lion would have done to balance the acid from consuming muscle flesh; instead they took their fill from the plentiful lean meat. Their instinct for the right food had long degenerated and native knowledge was apparently ignored.

One look at history is enough to understand the consequences of a prolonged excess burden on the liver and kidneys, without the need for “scientific studies”: in ancient times a popular form of death sentence was to administer muscle meat to prisoners without any alkaline food to balance it!

Ratio of Net Nitrogen Utilization (NNU) to nitrogen waste in food proteins in comparison to the MAP® food supplement developed by Prof. Dr. Lucà-Moretti.

Proteins Consist of Amino Acids

What are proteins? Proteins consist of small building blocks called amino acids. These amino acids consist of four chemical elements—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen and the oxygen atom—and are used by the human body to make thousands of different proteins that perform different functions. For example, the first complex protein discovered in 1851 by Otto Funke is the transport protein haemoglobin—the ferreous blood pigment of red blood cells (erythrocytes). It consists of more than 1,800 amino acid bonds. Macrophages (white blood cells), T-helper cells or glutathione (the vital antioxidant active in cells) also consist of amino acids. Amino acid groupings are only referred to as proteins by the scientific community if the complex comprises more than one hundred amino acid compounds; fewer than a hundred amino acid compounds are labelled peptides.

In total there are twenty proteinogenic amino acids. The body can synthesise twelve of these on its own; the other eight must be introduced through food. This is why they are also called the eight ‘essential’ amino acids.

The 8 Essential Amino Acids

These are L-Isoleucine, L-Leucine, L-Lysine, L-Methionine, L-Phenylaline, L-Threonine, L-Tryptophan and L-Valine.

In digestion, the body breaks down any proteins introduced through food with the help of enzymes (pepsin, trypsin, chymotrypsin). In the ideal case of optimal digestion, all the amino acids are assimilated by the blood and can be used by the body to build body protein. The constructive eight essential amino acids, along with the other amino acids produced by the body, form the structural foundation of our organism as well as all life-supporting molecules. This process is called body protein synthesis.

Proteins Form the Structure of Our Body

The term protein was derived from the Greek word protos (first, most important) or proteuo (I take first place) by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1839. As a mentor and friend of Gerard Johannes Mulder, he had been present at Mulder’s discovery of protein’s molecular structure as the standard “basic material” (using the german word “Grundstoff”) and suggested the term ‘protein’. With this word, the two scientists wished to emphasise the great significance of proteins for life.

David Raubenheimer, a food researcher and biologist at the University of Auckland, has highlighted the fact that there is an evident ‘protein hierarchy’ in human nutrition, which leads us to satisfy our appetite for protein before anything else. Although the amount of protein in food is tiny in comparison to fats and carbohydrates, the protein requirement for the human body takes priority. This should come as no surprise, since the building blocks of protein, amino acids, are involved in almost all vital functions in the human body: cell regeneration, enzymes, hormones, bones, cartilage, hair and nails, tendons and ligaments. As scleroprotein, they supply the collagen of our skin; as structural protein they supply our muscles; and as transport proteins (haemoglobin) they supply our blood.

Proteins are a vital component of our nutrition. Not only do they contribute to the regeneration of the body’s muscle and tissue cells, build and regulate hormones and enzymes and control metabolism, they also form the basis of our immune system and immune defence by helping us to ward off disease.

Proteins provide the basic building material for our entire organism. As already mentioned, about half of the body mass that doesn’t consist of water consists of proteins. Most proteins in our body are continually rebuilt, broken down and renewed, which is why our body must form thousands of proteins every day in order to replace those that have undergone this process.

The more active a person is and/or the higher his stress levels (perhaps through illness or top-level sporting performance), the quicker protein is broken down and the more new protein is required to replace it. Unlike carbohydrates (glucose) or fat, amino acids can only be stored short-term. The body’s own pool of amino acids is available for a maximum of two to three hours, so the body needs replenishment several times a day.