Have You Kissed a Snail yet Today?

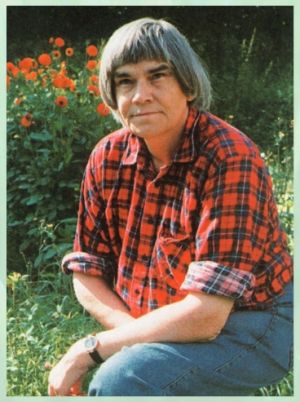

Yuck, you say. Well, you don’t have to go straight to kissing snails. But how about showing them a little affection? Eike Braunroth is a man who has learned to make friends with what we disdainfully refer to as ‘creepy crawlies’. It has turned his garden into a paradise!

Would you call yourself a peaceful person? Yes, I’m sure you would! You don’t hit your wife/husband or your children (the latter only as a last resort); you tolerate the barking of

the neighbour’s dog stoically and refrain from indulging in the eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth philosophy when you’re feeling harassed at work.

Anyone watching the tender love-play of two snails in the film ‘Microcosm’ is bound to feel that these little creatures have feelings too.

You only wage war in the most peaceful part of your home: the garden.

What did you say? Oh, I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to offend you. Of course, you never, never, never attack snails and ants, potato beetles and cabbage whites, rose chafers and rats, whitefly and corn borers, wild boar and voles—not with chemical or biological weapons of mass destruction and certainly not with ones that go bang.

But the war begins much earlier: inside your head. “Will I have a good harvest this year? Or will they (my enemies), the pests, feast away at my vegetables? My roses? My berries? What should I do to ensure they don’t get a chance to ravage, besiege and destroy my plants? Will the (hostile) rain flood my land, or (hostile) drought make it as hard as stone? Will the (hostile) elements claim victory or will I emerge stronger this time? Will I get it right? Will I feel that sense of achievement, with the boughs groaning under the weight of the fruit and the lettuces sitting there in plump, full rows?”

Let’s be honest: haven’t we all entertained such thoughts, felt such anxieties, questioned ourselves and the garden? To be honest, we act rather like generals in a minefield. The enemy is everywhere; right up to harvest time we cannot tell if the fruits of our labours will bring good yields—or if we will be defeated by snails, frost or pests.

We divide ourselves and the garden into two (hostile) camps. We try to bend nature to our will and see it as disobedience or even an outright challenge if nature does not do our bidding. We create separation between ourselves and the garden. We confront it with the attitude of one who makes nature his slave.

That would not be so very far wrong in theory. In practice, in his garden man lays down certain conditions that cause the laws of nature to become impersonal and they then have an effect that relates directly back to the basic conditions.

But hey! That would mean that man is to blame for the situation in his garden? That he is to blame for the plague of snails, for the voles and the potato beetles? Even for the weather, which doesn’t behave itself? Isn’t that going a bit too far? Am I really to blame for everything?

Make peace with nature

Let’s not talk of blame. We act according to our knowledge and our experience. If we learn something new we can act better and gradually find our way to a true ‘Cooperation with Nature®’, which is man’s true function and destination.

There is one man who has taken this path. His name is Eike Braunroth and he has

developed a ‘concept’ as simple as it is wonderful, as happy as it is successful (although

concept is the wrong word for it, rather one should talk of ‘attitude’), in which plagues of snails or ants, rats or silverfish, aphids and bark-beetles disappear ‘of their own accord’. The concept involves making true peace with nature. Not separating oneself from nature but seeing oneself as part of a whole—as a formative and masterful part, perhaps, but a part all the same, and not a feudal lord or a general.

Eike Braunroth was born into a family that was very close to nature. “Even as a child I felt a close inner relationship with nature”, he says. “I became aware of flower fairies and animal devas and I communicated with them. I felt at one with everything I saw and heard.” He was given his first patch of garden upon starting school in 1946. He sowed marigolds, beans, peas, radishes and many wild herbs such as shepherds purse and dandelions. “There were no ‘pests’ here. All creatures were welcome.”

As he grew up he lost that ‘inner vision’. “I found myself in a state of consciousness where I was detached from nature. From adolescence onwards, snails and later potato beetles, blackbirds and bark-beetles made themselves ever more conspicuous through their huge appetites.” Like us all, he too began to fight against these ‘pests’ and to defend ‘his’ garden. Hopeless. The turning point only came when he heard about Findhorn. “From my knowledge and theirs I entered into a new relationship with nature. Not fighting, nor connivance but cultivation of a caring association.” This was the starting point

for his ‘Cooperation with Nature®’ approach that anyone can learn today.

As previously mentioned, our bad attitude starts in the mind. With our expectations of anxiety and doubt: will I get a good enough harvest? Will the whitefly stay away this summer or will they once again spoil my joy in my plants?

If we think like this, says Eike Braunroth, we create an etheric field that is charged with destructive elements. “On an etheric level in the morphogenetic field this anxiety also manifests itself in the plants. Cultivated plants are therefore directly dependent on the person they ‘belong’ to. They cannot decide for themselves. They simply react to his anxiety. They grow weak. They get sick. According to cosmic law this inevitably leads to other organisms—those that we think of as pests—‘destroying’ the plants, or rather transforming them into another, higher state of being.”

Eike Braunroth, friend of bark-beetles and greenfly, for whom slugs extend their feelers in his presence rather than draw them in fearfully—as they do with people who are hostile to them.

their children and themselves.”

Yet how arrogant to declare that certain beings of creation are simply ‘pests’! What do we really know of the functions performed by these creatures? Eike Braunroth’s experience is that, firstly, ‘pests’ are the direct consequence of our own negative attitudes. And, secondly, that they respond to war with war. If, however we manage—admittedly not without some difficulty—to see them as partners in our garden, whose entire reason for being is to fulfil some task that we may not even recognise—and if we even manage to treat them with the same respect and love that we offer to our dog or our cat, then their behaviour will change completely.

“A couple of years ago, when I needed a lot of snails for a talk I was giving, my garden did not have very many so I ordered a whole load from a snail hater”, Eike Braunroth recalls. “He promised me a whole boxful and even sent his children into the garden to get them. When the snails had been delivered I welcomed them, took the pierced lid off the box and sprinkled the exhausted creatures with rainwater. Straight away there was an enormous snail invasion in the garden—and they were never seen again. Even upon close examination there were no more snails to be found in the garden than before, and no

useful or edible plants were devoured. The garden of a peaceable gardener with its peaceable atmosphere had turned the supposedly voracious monsters into frugal creatures.“

People cause the forests to suffer

Eike Braunroth has a whole collection of similar happy experiences. One concerns potato beetles: “We were holding a Trilogy Seminar on a farm in Austria. At this time, a field was

being planted up with potatoes. During the care seminar in the summer we counted 31 potato beetles in the whole field, all of whom were mating like mad. We monitored the underside of all the leaves of the potato plants after the eggs had been laid and over the next few weeks one of the seminar participants was given the job of looking for eggs and larvae. Neither we nor the participant found eggs or larvae.“

Braunroth’s explanation for that is completely obvious to open-minded people: “The question of what happened to the pests is the wrong thing to ask. In the right context it can be seen that the animals, in their whole attitude to life, are able to switch off the urge for reproduction and voraciousness because man’s love induces such an ethereal rhythm in them that their anxiety is turned around and switched off.”

In the same way, the ‘bark beetle plague’ that threatens our forests is also closely tied up with man’s relationship to the woods. “The absence of friendly people, their distance and the reduction of this sense of cohabitation to a mere wood factory has caused the forest to

fall ill”, concludes Braunroth. Gone are the days when romantic po ets and composers sang about the woods and talented artists painted them in the most beautiful colours. The forest has become a pure profit centre—with disastrous consequences.

Add to that “the decade-long battle of mankind versus the fox, who along with its cubs is never safe at any season but hunted the whole year round. Add to that the decade-long battle against the organisms that cause symptoms of rabies or Lyme disease in people,

the years of battle against bark beetles, green oak roller moths, gypsy moths and black

arches moths. It is mankind’s battle that strengthens these organisms and weakens the forest. It does not start with the fight itself but with the planning of the ‘campaign’ against

certain woodland organisms. Harmful air pollution merely speeds up the dying

process. A healthy forest”, says Braunroth, “needs care, love and people who work in it with understanding—in Cooperation with Nature®, people who go walking in it and children who play and make happy noises.”