Why the Ark of the Covenant isn’t in Ethiopia

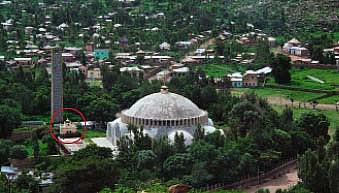

The gigantic Aksum Cathedral. Close by is the Church of Our Lady Maria of Zion where the Ark of the Covenant is supposedly kept (red circle). Although the Ethiopians claim to possess the Ark of the Covenant, no one has been allowed to see it.

When he was grown, he traveled to Jerusalem to meet his father. Impressed by his magnificent son, Solomon tried to convince him to stay and one day become king of Israel. However, Menelik declined his offer in order to return to Aksum and rule. Before he departed, the wise and calculating Solomon anointed Menelik King of Ethiopia in a Jewish ritual. In order to ensure his influence over Ethiopia, Solomon sent the sons of his highest priests and officers with Menelik as his closest advisers to the Ethiopian court in Aksum where they were to implement the jewification of the Ethiopian kingdom. Yet in Jerusalem, these young people had been serving the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the divine Stone Tablets. Because they did not want to shirk this holy task, they snatched the Ark of the Covenant from the temple with the help of an angel and brought it to Aksum where it supposedly remains to this day. Menelik became king and forefather of the Ethiopian rulers, whose Solomonic lineage was maintained with just one disruption up to Haile Selassie.

A myth? Of course, but it is certainly even more than that. The ancestry of the Ethiopian regents stemming from the tribe of Judah and the Queen of Sheba was not only “authenticated” as absolute truth in the empire because of their official titles. Haile Selassie also locked this claim into place in the new 1955 version of the constitution. Their validity ended when Selassie was overthrown.

This historical tradition is still alive today in the consciousness of the Christians that dominate the Ethiopian population. The Ark of the Covenant with the Mosaic Stone Tablets play as much of a central role in their beliefs and worship today as they did back then. If we want to believe the Ethiopian priests, the original rests in The Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Aksum, yet proof is not readily available since no one is allowed to see the sanctuary with the exception of the watchmen who constantly stand guard. All of Ethiopia’s churches, however, house replicas of the Tablets and are called Tabots. These Tabots are displayed in public during important holidays such as the Timkat festival, but are veiled with expensive cloths made of gold and silver brocade making only the wooden or stone shape of the tablets visible.

It is unlikely that the Timkat Festival was taken from the Old Testament and passed down these last 3,000 years from the time of Solomon. When we compare historical dates and facts with the legends, it is difficult to find points of agreement. Solomon reigned from 963 to 925 BCE yet the Ethiopian dynasty in Aksum was founded in the middle of the 1st century AD. The israelitic Ark of the Covenant stayed in the temple in Jerusalem until the Babylonians destroyed it in 586 AD. With this historical background it is understandable how and why such legends originate in the first place.

It was essential for Ethiopia’s history that the culture of the heartland was based on a Southern Arabic foundation rather than an African one, hence the Kingdom of Sheba. In the 6th century BC, immigrants began to travel from here over the Red Sea and established themselves as farmers. The Amhara and Tigray people emerged from Sheba immigrants and the indigenous population and founded the Aksum Empire in the 1st century AD. They adopted Christianity 300 years later. In the 10th century, Jewish conquerors assumed governance. The Christians were forced to adapt to Jewish religious customs and rituals whether they wanted to or not. However, they infiltrated the conquerors with their culture, which resulted in many cross-overs between the two denominations that resonate into the modern day.1

Sources

- 1 Ekkehart Rudolph, On the Trail of the Ark of the Covenant—The Queen of Sheba in Ethiopia—A Legend and its Historical Background, in www.epochtimes.de