Federal Reserve: Banker's Discretion

Why our money is no longer what it was—and who it belongs to.

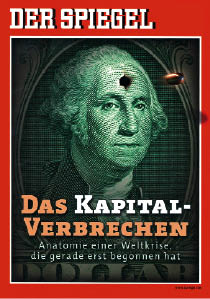

The Capital Crime: the economic crisis isn’t just an attack on America’s fortune—it’s also an attack on its true values.

“I am afraid that the ordinary citizen will not like to be told that the banks can, and do, create and destroy money. And they who control the credit of a nation direct the policy of governments, and hold in the hollow of their hands the destiny of the people,” remarked insider Reginald McKenna, chairman of the [former] Midland Bank in London. Of course, the “common folk” have no idea what’s going on. They are too innocent to even begin to fathom the perfidious game in which the people of the world are merely pawns.

In the Eye of the Storm

Whereas the dictators of money used to be found in the City of London, the world’s financial system is today dominated by Wall Street. Some of our readers will know that the Federal Reserve System, the central bank of The United States, is a deceptive package and in no way belongs to the people or the nation, but to—well, whom? This is difficult to determine, because it’s private—and therefore no one’s business! One thing is for sure: the U.S. government does not hold a single share of stock in the Fed. German Author Michael Grandt (“State Bankruptcy is Coming”, available only in German) reveals that even the name Federal Reserve Bank is a triple lie: “federal” means recognising the sovereignty of a central authority whilst retaining certain powers of government, yet the Fed doesn’t belong to the U.S. government. The owner is a consortium of private banks, of which the biggest are well-known: Citibank and J.P. Morgan Chase Company. Even the judges of the Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that the Fed is privately owned.1

The name “Reserve” suggests that the Fed has money in reserve. Grandt: “That is incorrect. It has absolutely no reserves.” Even in the 1960s, former congressman and chairman of the House Banking Currency Committee, Wright Patman, wrote in a report: “The cash, in truth, does not exist and never has existed. What we call ‘cash reserves’ are simply bookkeeping credits entered upon the ledgers of the Federal Reserve Banks. These credits are created by these Federal Reserve Banks and then passed along through the banking system.”

So where does the Fed get the money to buy U.S. government bonds? Patman also wondered about this and came to the conclusion: “The Fed doesn’t get any money, it creates it [i.e. out of thin air, Ed.]. It creates money purely and simply by writing a cheque. When the recipient of the check wants cash, then the Federal Reserve can oblige him by printing the cash—Federal Reserve notes—which the check receiver’s commercial bank can hand over to him. The Federal Reserve, in short, is the perfect money-making machine.”

Grandt quotes economist Prof. Dr. Hans J. Bocker on the power of the Fed to create money, with the following words: “The dollar is a private currency; the U.S. has no federal currency. The real estate of all U.S. states serves the Fed as a deposit.”

Nine Out of One

If the private bankers owning the Fed decide to print more money, it costs them only the ink and the paper it’s printed on (which is about three cents a dollar)—while they sell the nation dollars as credit, on which people must then pay interest. The Federal Reserve thus has absolutely no obligation to protect the American currency and economy (and thus the American people) from any form of hardship. No wonder Allan Meltzer, Professor at the Carnegie MellonUniversity in Pittsburgh was moved to comment: “I do not know of any clear examples in which the Federal Reserve acted in advance to head off a crisis or a series of banking or financial failures.”2

What most people don’t realise is that the banks can create money out of nothing like a magician conjures doves out of a handkerchief. The Fed permits banks to do this at a ratio of one to nine (1:9). Michael Grandt explains this in his book as follows: “This means that for every dollar taken to the bank, nine dollars can be created.” He continues, “Ten per cent of the pay check paid into a worker’s account is retained as a reserve. The remaining 90 per cent is loaned out and credited to another account, and this amount is therefore credited to the bank as additional real money. From this sum, another ten per cent can be retained and 90 per cent loaned out, etc. In fact, this money only exists in computers. What doesn’t exist merely virtually, however, is the interest paid on precisely this ‘created’ money. Also real is the car or house that has to be handed over if the interest can no longer be paid on such credit. The parts of the financial system that have true value ultimately go from the citizen to the banks and not the other way around. Incidentally, the ratio has increased and is today one to eleven. It is therefore little wonder that financial institutions even encourage risky credit, because the only thing they can make money on is the interest. So why should they demand early debt payment?”

And so we find ourselves living in a monetary system of debt: a bank only increases its balance by reallocating money as credit an indefinite number of times. It makes its “turnover” by loaning credit—nine or eleven times as much as it has real paper. This is completely unreal money not covered by anything—not gold, not silver, nor even work or economic performance. It is basically Monopoly money that only maintains its “power” because members of the public are forbidden to print their own money (or federal money) on pain of prison sentences, or even to open up their own bank for the neighbourhood. The biggest threat for a bank is therefore its assembled clientele, which storms to the counter and demands its credit. This kind of “mass panic” is the dagger thrust for a financial institute, 90 per cent of whose wealth consists merely of numbers on paper or on a screen—or in second place, real values (real estate, plots of land, companies), which its customers have built up in the real world with this borrowed unreal money. Note: each small-time borrower must offer the bank a security of some description—land, house, guaranteed inheritance—in order to get the money that only exists as long as all the other bank customers don’t lose their trust in the bank and reclaim their savings. If that happens, the borrower can expect absolutely no security from the bank. In that case, if worst comes to the worst, the State must step in—as German Chancellor Angela Merkel did during the heated times of crisis when she promised citizens that their savings balances were secure—thus preventing a run on the banks, as had taken place elsewhere.