Organ Donation - Modern Cannibalism?

There’s no such thing as brain death; it’s an invention of transplant medicine.

Professor Franco Rest

If we told the public the truth about organ donation, we would no longer get any organs.

Rudolf Pichlmayr, Professor of Transplant Medicine

A holiday in Austria, France, Italy, Spain, or Sweden hides dangers that few holidaymakers will be aware of. Those suffering the misfortune of a near-fatal accident and being taken to a local hospital, being diagnosed with “brain death”, will find themselves gutted from groin to throat. Their hearts will be taken, as well as their kidneys and liver. If the doctors need it, and if the organs are still relatively young and healthy, they will also find their small intestine snatched from them. Not only that, but their pancreas, stomach, corneas, and femurs too; not to mention tissues like skin, blood vessels, heart valves, the pericardium, ligaments, or joints and other bones.

What’s that you say? You’d never consent to having your organs removed? Well, the surgeons in the countries mentioned don’t care in the slightest. After all, you’re hardly going to be in a position to object, and the protests of your next of kin will be worthless. The only thing that can protect you from having your internal organs stolen is to carry a non-consent form with you, or to have yourself registered as refusing to donate in the databases of the respective countries. Of course, that’s the last thing to cross your mind when you’re packing your swimming trunks before heading to the Costas, or your walking boots ready for the Austrian Alps.

Okay, you might say, it’s hardly an appealing prospect – but at least my dead body is going to be put to good use. Hold on a minute: you might be diagnosed as “brain dead”, but your body remains very much alive. The only thing that stops working is the brain. Your heart keeps beating. You can still sweat or get cold, stir and roll over in bed. Men can even get an erection, and ten cases have been officially documented of pregnant women giving birth, after weeks or even months of ‘brain death’.1

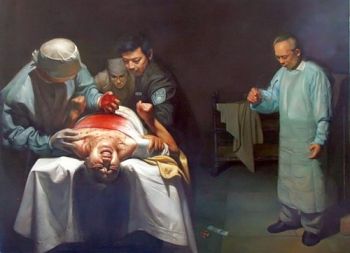

A dramatic portrayal of an organ removal operation in China, the world leader in ‘organ harvesting’.

And that’s what it was, until the day in 1968 when a commission at Harvard University decided that there is such a thing as ‘brain death’, a state from which the patient can never recover, finding themselves in an irreversible coma. The basis for this decision lay in the heart transplants first carried out by the South African Christiaan Barnard on December 3rd 1967. They naturally entailed taking a living, beating heart from an accident victim or someone in the final stages of illness, and therefore killing them.

This had been picked up on by public prosecutors in several countries, who made a case for wilful killing. Something had to be done otherwise legal constraints would put a stop to organ transplantation. So it came to be that – in hospital – a human being is no longer dead when their pulse and respiration have ceased once and for all, rigor mortis and livor mortis have set in, and spirit and soul have visibly left the body. Instead, it is when the brain ceases to function. According to the doctors, this is the point at which the warm, breathing, heart-still-beating body can be wheeled into the operating theatre – to be taken apart with scalpel, saw, hammer and chisel. Blood shoots out in high fountains, and to quieten the still-living organism, 15 litres of ice-cold water are poured as quickly as possible into the torso. The organs are then cut out one by one.

The patient is normally tightly strapped down during all of this, because the living body rises up and tries to defend itself against the outrage being inflicted on it. An anaesthetist injects muscle relaxants into the body; in Switzerland they go so far as to administer a general anaesthetic. The German Organ Transplantation Foundation recommends the use of fentanyl, an artificial opiate, “to optimise the surgical procedure”. Fentanyl is around one hundred times stronger than morphine. Food for thought! A rise in blood pressure, pulse and adrenalin can all be measured in these supposedly dead bodies: during normal operations, these would all be seen as unambiguous signs of pain and distress.

The operating theatre is full of staff – the organ customers have come from all over: medical personnel who put the liver, the kidneys, the heart on ice then rush off as fast as possible to a critically ill patient awaiting salvation. When the German SPD (left-of-centre party) MP and medical doctor Dr Wolfgang Wodarg expressed interest in attending one of these organ removal operations, his request was rejected. The reason given: the battlefield-like scene would be too much for any outsider.

Because of the ‘donor’s’ almost complete blood loss and consequential overflow of blood and icy water, the surgeons usually stand on mats or cloths during the operation. Subsequently, the gutted and now genuinely dead body (thanks to its hollowness, the medical staff call it, with dark humour, a “rag doll”) is stuffed with all kinds of padding: broomsticks, filler, glass beads if necessary, to restore some kind of halfway human aspect to the corpse.

Saved At The Last Moment

Even the methods used to diagnose ‘brain death’ cause unnecessary, even inhuman pain to people who are not really dead, and therefore still sensitive to pain. These include pricking the inside of the nose, irritating the cornea using a blunt object, exerting firm pressure on the eyeball, pouring ice-cold water into the ear canals, and irritating the bronchi with a catheter. Sometimes, medical staff go so far as to conduct an angiography, 2 which in living donors can lead to anaphylactic shock resulting in death.

Last of all comes the respiratory failure (apnoea) test. The doctors switch off artificial ventilation and observe whether a breathing reflex sets in in the next four to ten minutes. If that doesn’t happen (in the meantime, oxygen is being fed directly into the trachea), the patient is declared to be ‘brain dead’.

But not really dead, as transplantation specialist Werner Hanne stresses in his writings. He explains: “When it comes to ‘organ production’, the apnoea test is the riskiest: the patient must not ‘really die’ during this test (circulatory collapse). If this happens, resuscitation will be attempted if necessary. If the apnoea test proves negative, i.e. there is no spontaneous respiration, then the two doctors present, by means of their signatures and a date and time, transform a patient who was alive up until that moment into a ‘corpse’ from whom organs can be removed.”

“If the patient still isn’t brain dead after all these tests (for example if respiration restarts), then it’s just their hard luck having had to go through this torture twice. The patient is then regarded as a ‘normal’ coma patient again. However, the tests will be repeated at a later date. And the time of death is perfectly flexible. If one weekend, for example, no one is available who is qualified to diagnose brain death, then the assessment of death will be correspondingly postponed. The paradox: the heart-lung machine saves the patient, two signatures kill them.”

All the more horrifying, then, that on many occasions, ‘brain dead’ patients have come back to life, including these cases from the past few years:

• A nurse who saved a donor’s life before the organs could be removed as planned, asked the doctor in charge why he had left the room at the critical moment. The doctor’s response was that he had not wanted or been able to recognise the patient’s vital signs, because his thoughts were already with the organ recipient. Thanks to the attentiveness of the nurse, the involuntary organ donor survived the debacle, albeit in a wheelchair.3

• After misdiagnoses in Germany and the Netherlands, patients were saved from organ removal at the last minute. They are now healthy again. The Christian weekly magazine idea-spektrum4 reported: “During her research, the Munich-based television journalist Silvia Matthies came straight across two cases where patients were to be cleared for organ donation: in Holland, building contractor Jan Kerkhoff; in Freiburg, a young American soldier. In one case the family intervened; in the other a nurse – and the patients continued to be treated. Both were able to leave hospital a few weeks later…”

• In France, a 45-year-old survived because the doctors were temporarily held up. He had already been laid out on the operating table, ‘ready’ for organ removal. (France is among those countries where every ‘dead’ body can be eviscerated, provided no non-consent form is carried). The man had been declared dead after a cardiac arrest. “The surgeons didn’t have time to deal with the supposed corpse straight away. Lucky him: just before organ removal began, his heart started beating again. The fact that the paramedics brought him to the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris nearly proved his downfall. The hospital is one of nine nationwide taking part in an organ donor pilot project. Because his heart wasn’t beating independently and the doctors decided that they couldn’t widen his coronary vessels, the patient ended up in the operating theatre as an organ donor after only an hour and a half. As the surgeons were about to begin incision, the supposed dead man suddenly started breathing again, and his pupils reacted to light.”5

So the saws were set aside. Afterwards, the Frenchman was able to walk and speak normally, and lead, given the circumstances, a perfectly normal life. He had given himself the gift of life with his timely awakening.

In order to get at organs as quickly as possible, France and Spain consider cardiac arrest to be sufficient grounds for organ removal. This also applies to foreigners (e.g. anyone falling victim to a fatal accident in France or Spain).

After a serious car crash, a 21-year-old American was cleared for organ removal. His parents, who were present, gave their consent. The comatose, paralysed young man heard and understood everything, as he later recounted: he would have liked to have leapt from the table. He thanked his survival to delays to the organ transport flight, and the attentiveness of his cousin, there to say her goodbyes.

In 2007, Focus magazine reported a case in Venezuela where the ‘corpse’ suddenly started breathing at the beginning of an autopsy.

Sources

- 1 Sabine Müller, Ph.D. M.Sc., Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Revival der Hirntod Debatte ("The Brain Death Debate Revisited") appeared in the journal Ethik in der Medizin ("Ethics in Medicine")

- 2 A contrast agent is injected into the blood, then an X-ray or MRI scan is used to visualise the distribution of blood in the body.

- 3 Source: ZDF film report Organspende - der umkäpfte Tod ("Organ donation - The Disputed Death"), 7/4/1994

- 4 No. 12/2007.

- 5 http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/mensch/umstrittene-spenderauswahl-schon-herzstillstand-reicht-aerzten-fuer-organentnahme-a-559972.html