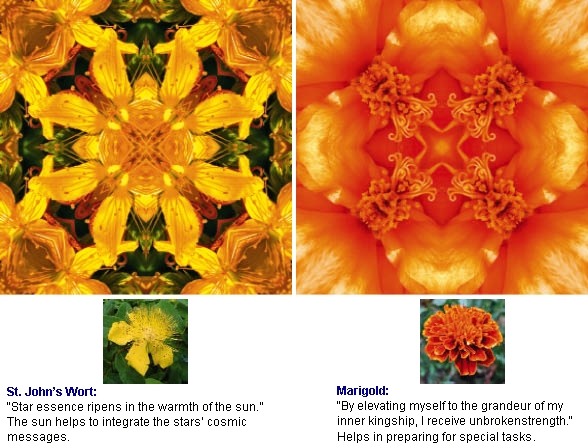

Imagami: Blooms of Dreams for Human Souls

“Flowers are the beautiful hieroglyphics of nature, with which she indicates how much she loves us,” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once wrote. Experience pictures by a man who strives to depict the souls of flowers and trees for the good of our own.

“Plants are living antennae for comsic-atmospheric influences,” wrote Swiss holistic health practitioner Dr. Jürg Reinhard very rightly. They all absorb different energy frequencies from sunlight, which of course also contains all mineral elements on the level of vibration. We know from homeopathy and Bach flower remedies that every plant embodies a certain spiritual quality. True religion tells us that this is no coincidence, as the natural realm sees itself as mankind’s humble servant. In fact, they represent “God’s wonderful pharmacy” for their masters, abundantly filled with everything we could possibly need to heal body and soul.

You can absorb healing remedies through all five senses: you can swallow, inhale, or transmit them through touch—you can even hear them as healing sounds. And what about sight? It constantly assimilates vibration and channels it through the eyes to our inner being, because everything that exists emits a continuous subtle energy. So for example the quality of destructive radioactivity can be picked up even in an ordinary living room if the TV screen is showing a mushroom cloud. Kinesiology has shown us that an audience visibly loses strength if there is a picture of a smoker on screen, even if there is no smoke or cigarettes actually in view. If, on the other hand, our eyes glide over a beautiful landscape untouched by ugly human creations, our inner being respires and draws strength. As soon as just one power line crosses our line of sight, the entire healing effect ebbs away.

Pictures are Linked to What They Display

In the summer of 1951, Curtis P. Upton, a Princeton-trained civil engineer, and his Princeton classmate William J. Knuth, an electronics expert, undertook a unique experiment. They drove into the cotton fields of the thirty-thousand-acre Cortaro-Marana tract near Tucson, Arizona. Together they unloaded from the back of their truck a mysterious boxlike instrument about the size of a portable radio, complete with dials and a stick antenna. They would attempt to affect the field not directly but through the medium of photographs.

An aerial photograph of the field was placed on a “collector plate” attached to the base of the instrument, together with a reagent known to be poisonous to cotton pests. The dials were set in a specific manner. The object of the exercise was to clear the field of pests without recourse to chemical insecticides.

The theory behind the system—as “way out” as anything so far reported on the nature of plants—held that the molecular and atomic makeup of the emulsion on the photograph would be resonating at the identical frequencies of the objects they represented pictorially.

It would have been hard to find a scientist who would bet the small change in his pocket that Upton and Knuth’s protective process could offer them any safeguards against marauding pests. Yet, in the fall, the Tucson Weekend-Reporter ran an illustrated two-page spread headlined: “Million Dollar Gamble Pays Off for Cotton Man”. The article stated that a “Buck Rogers type of electronic pests control” had allowed Cortaro to achieve an almost 25 percent increase in per-acre yield of cotton over the state average.

On the East Coast of the United States, one of Upton’s Princeton classmates, Howard Armstrong, who had become an industrial chemist with many inventions to his credit, decided to try his friend’s method in Pennsylvania. After taking an aerial photograph of a cornfield under attack by Japanese beetles, he cut one corner off the photo with a pair of scissors and laid the remainder together with a small amount of rotenone, a natural beetle poison, on the collector plate on one of Upton’s radionic devices.

After several five- to ten-minute treatments with the machine’s dials set to specific readings, a meticulous count of beetles revealed that 80-90 percent of them had died or disappeared from the corn plants treated through the photo. The untreated plants in the corner cut away from the photo remained 100 percent infested!…1

Sources

- 1 From: Tompkins/Bird, The Secret Life of Plants, page 159 ff.